FOCUS - Extreme researchers 2024

Extreme researchers :

exceptional environmental and physical conditions

What is a researcher's life and daily routine? What makes their research qualitative? What makes the difference?

On the occasion of the Printemps des Sciences on Thursday 18 April 2024, Secondary school pupils will have the opportunity to meet the people involved in research face-to-face at career speed-dating sessions. It's an opportunity to look at the profession from all angles.

Research is often portrayed in lab coats, with test tubes, analysis and studious reflection, far removed from the image of the trained explorer. However, researchers often do not study what is within their reach. To reach the unattainable, they prepare for extreme living conditions, train to cope with the demands of an environment that is not their own, and put their physical and mental strength to the test to achieve goals that match the ambitions of science.

He swaps his lab coat for the hyper-technical equipment of the explorer, the same equipment that enables him to climb summits, acclimatise to unprecedented temperatures, descend into the bowels of the earth and defy the elements of water, fire, earth and air.

In the field of environmental geoscience, we need to be prepared for the many challenges that lie ahead. Those involved in research at CEREGE can testify to this.

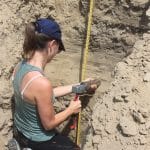

Julie LOSEN, Doctoral student in the Earth & Planets team, CEREGE

= Trekking, hiking, climbing during field missions in isolated areas

Vincent JOMELLI, Research Director, Climate Team

= Trekking, hiking, climbing during field missions in isolated areas

I did a lot of international fencing when I was young. As this sport is exclusively competitive, it undoubtedly helped me to pass the CNRS entrance exam, as I was never a good student. The mountains are a family sport, so after the baccalaureate I dedicated a sabbatical year to climbing. I had a decent level of climbing and was a trainer in a club, which enabled me to finance my university studies, as I came from a modest background.

Today, all my missions are carried out in isolated environments and sometimes at high altitude (> 6000 m). Travelling in tents, we stay at altitude for long periods and carry heavy loads every day. To access some of the study sites, mountaineering (climbing walls or glaciers) is compulsory. Sport is therefore central to the success of the fieldwork. Researchers tend to be sedentary when they're not on assignment, so it's essential for their own safety to keep fit by practising this activity regularly throughout the year. This gives you a «buffer» when it comes to managing the effort and stress associated with mountain hazards (lightning, avalanches, falls, altitude sickness, etc.) and maintaining good group cohesion even in difficult conditions. Regular climbing has also taught me to be persistent despite the difficulties, and not to doubt certain choices, even if success doesn't come immediately.”

Yannick GARCIN, IRD, Climate team researcher, CEREGE

= Trekking, hiking, mountain biking

The Congolese Cuvette Centrale, which is currently the focus of my attention, is a hostile environment made up of vast swamps that are home to the largest tropical peat bog on the planet. This very flat area, where the soil is waterlogged all year round, is covered by dense swamp forest. To reach our study area, we can travel for up to three weeks by motorised dug-out canoe along rivers, sleeping in tents. To access the peat bogs from the rivers, we travel very slowly, for days on end, carrying heavy rucksacks containing our equipment and samples. The peat quickly gives way beneath our feet, leaving very dark water rich in coarse plant debris to unpleasantly invade our boots. In these conditions, it becomes very difficult to walk.

The landscapes often resemble a giant Mikado, where in order to move forward you have to jump over collapsed tree trunks, entangled one on top of the other, and in the process of decomposing, which finally break every other time under your feet. The very high air temperature and relative humidity, the venomous fauna encountered and the sharp vegetation all add to the difficulty of this environment. You need to be agile and in good physical condition to move around in this hostile environment and to get the heavy corer into the peat to bring back the longest possible core.

Deborah VERFAILLIE, Head of Research, Climate Team, CEREGE

= Trekking, hiking, glacier trekking on field missions in isolated areas

At present, I'm working more on palaeo aspects, collecting samples from boulders in glacial moraines to date glacial palaeo-retreats by measuring cosmogenic isotope concentrations in these rocks using the ASTER accelerator mass spectrometer.

When I was young, I swam at a high level, which gave me stamina and a sense of competition, but also of team spirit. When I was 7 or 8, I discovered the black and white expedition photos of my paternal grandfather, who died before I was born. He was a researcher and took part in the Belgian polar mission to Antarctica in 1958 to mark the International Geophysical Year. I've been interested in the southern regions ever since, and I'm very happy to have been able to make a career out of it!”

Laurent DRAPEAU, Research Engineer, Sustainable Environment team, CEREGE

=

”As a research engineer in applied mathematics and spatial remote sensing, I work on the implementation of digital, geostatistical and spatial methods for the management and monitoring of socio-ecosystems. For 10 years I ran a hydro-nival observatory, i.e. on snow cover and climate. A lot of high-altitude terrain, access steps, installation of stations in areas that are difficult to access and maintenance.”

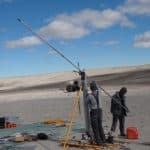

Jérôme GATTACCECA, Director of Research, Earth and Planets team, CEREGE

= bivouacs in isolated desert environments

All these missions in extreme environments are not sporting feats, as they essentially involve walking in relatively flat areas. That said, if you're going to walk several hundred kilometres during a mission, sometimes 20 to 40 km a day, a good level of physical fitness is an asset if you want to have a reserve of energy available despite the nights in a tent, for the many other aspects of the fieldwork, and in particular for managing the group. Indeed, in these extreme and isolated environments, where paradoxically a certain promiscuity reigns during the missions, the cohesion of the group is an essential element of success. Other keys to the success of this type of mission are the choice of the right partners, thorough logistical preparation, knowledge of the dangers and appreciation of the risks inherent in this type of environment. Preparing for the field operations themselves, with maps and work programmes, is also necessary, even if it generally comes up against the unpredictable nature of the terrain very quickly, requiring constant adaptations.

These missions in isolated environments have been key moments in my professional life, as adventures that have brought me to marvel at the beauty and power of nature, but also as human adventures shared in particular with my geophysical colleagues at CEREGE, Yoann Quesnel, Pierre Rochette and Minoru Uehara.”

Thomas STIEGLITZ, Director of Research, Resources, Reservoirs and Hydrosystems team, CEREGE

= Canyoning, climbing.

Alexandre Zappelli, Research Engineer, Resources, Reservoirs and Hydrosystems team

= Hiking, caving, aquatic environments (rivers, torrents, canyons), vertical environments.

Florence SYLVESTRE, IRD Research Director, Climate Team, CEREGE, represents the Institute in Chad, where she is based at the University of N'Djamena.

= Trekking, hiking

Previous Focus articles

Florence Sylvestre

From Andean paleoclimatology to Sahelian water management