1 million years ago, a migratory wave of humans (homo erectus) and animals (large mammals) from the east swept across the northern Mediterranean in a bid to conquer new territories. At the time, the ecosystems they were targeting to ensure their survival were wetlands, veritable oases of life and potential food in a generally arid Mediterranean environment. The tufa of Marseille (Bouches-du-Rhône, France), with its ecological diversity, its edible plants including proto-cereals, fruits and herbaceous plants, and its water resources, was a favourable site for this migratory dynamic.

A scientific article published in Geosciences by Valérie Andrieu, professor at the University of Aix-Marseille and member of CEREGE, and her colleagues from the Universities of Aix-Marseille, Montpellier and Malta, proposes a reconstruction of the palaeoenvironment of Marseille at the beginning of the Pleistocene, 1 Ma ago, thanks to a multidisciplinary study of the fluvial tuffs in this basin.

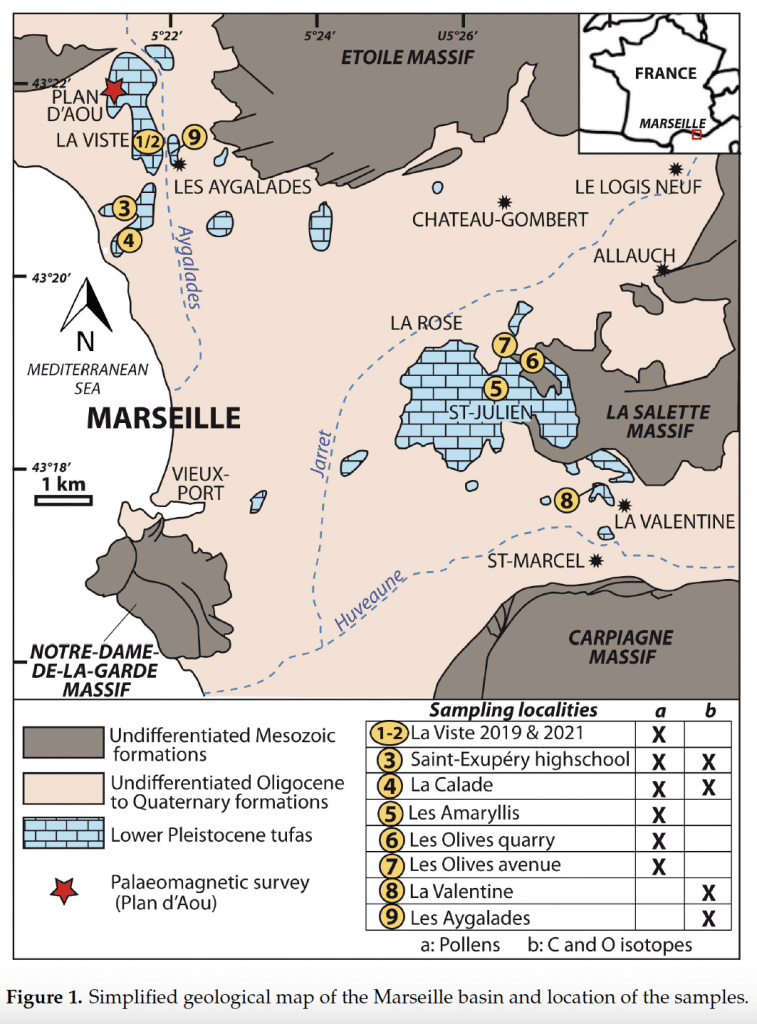

Palaeomagnetic measurements have identified the Jaramillo magnetic inversion and dated the Marseille tuff to between 1.06 and 0.8 Ma. The sedimentological data show the existence of a varied depositional environment including natural dams formed by accumulations of plants stabilised by carbonate precipitation, favouring the development of upstream bodies of water within marshes.

Carbon isotope ratios indicate that the Marseille tuffs are not true travertines but tuffs deposited by cold water springs.

Climatic reconstructions based on pollen data indicate a climate that is slightly cooler (especially in winter) and wetter than the current one.

Analyses of fossil pollen indicate a semi-arboreal, diverse, mosaic plant landscape, dominated by a Mediterranean forest of pine and oak with beech, fir and spruce, species that are now rare or no longer grow at low altitude in Provence, mainly due to human occupation. The presence of the chestnut tree is unexpected in a limestone environment, but this tree was able to grow on the decarbonate clays of the Oligocene, which outcropped everywhere in the Marseille basin.

Along the rivers, the riparian forest was diversified and included walnut and plane trees, as is the case today in the eastern Mediterranean, and trees such as alder, willow, hazel and ash. The potential diet of the first hominins, which we have reconstructed from pollen and plant macroremains, was varied and included the fruits of chestnut, hazelnut and walnut trees, as well as arborescent Rosaceae such as various species of plum and apple trees. Remains of vines have also been found, showing that grapes were already part of the diet of frugivores, including hominins.

Among the many edible herbs identified are the Compositae, which include many salads, nettles and mallow, a plant particularly popular in North Africa. Populations of hominins could potentially feed on resources from the sea, which were diversified at the time, and on land resources, including large herbivores.

The most surprising discovery was the presence of cereal pollen (proto-cereals because of their age), including rye, which was identified. These proto-cereals, which grew as part of the steppe herbaceous procession, were able to substantially enrich the diet of mammals (including hominins) that frequented the Marseille basin a million years ago with carbohydrates.

The Marseilles basin is the third site after those of Acigol and Kocabas (Andrieu-Ponel et al., 2021), in south-western Anatolia, to show the presence of proto-cereal pollen well before the start of the Neolithic period 12,000 years ago. The identification of spores of coprophilous fungi shows the presence in situ of herds of large herbivores.

It is possible that, as in Anatolia, the disturbance of ecosystems by large herbivores was responsible for the genetic mutation of Poaceae and the appearance of cereals. These sites show that the appearance of cereals was not caused by human populations, but rather by a natural process linked to biotic interactions between populations of large herbivores and steppe ecosystems.

In the Neolithic period, mankind, having become farmers out of necessity due to the reduction in mammalian fauna, would have cultivated edible plants that pre-existed in herbaceous ecosystems. This new discovery of proto-cereals requires a new vision of the history of human nutrition, as we suggested earlier (Andrieu-Ponel et al., 2021).

. Valérie Andrieu, Pierre Rochette, François Fournier, François Demory, Mary Robles: Aix-Marseille Université, CEREGE, 13545 Aix-en-Provence, France

. Odile Peyron, Séverine Fauquette: University of Montpellier, CNRS, IRD, 34090 Montpellier, France

. Eliane Charrat, Aix-Marseille University, 13545 Aix-en-Provence, France

. Pierre Magniez, Aix Marseille University (AMU), CNRS, Minist. Culture, INRAP, LAMPEA, 13090 Aix-en-Provence, France

. Belinda Gambin, Samuel Benoît De Coignac, Institute of Earth Systems, University of Malta, MSD 2080 Msida, Malta

Publication

Geosciences, 7 August 2024

Vegetation, climate and habitability in the Marseille basin (S.E. France) circa 1 Ma

See the article on the CNRS Terre et Univers website

Contacts

Valérie AndrieuCEREGE